How Useful are Perception Indices of Corruption to Developing Countries?

Posted by David Fellows[1]

The value and limitations of perception indices

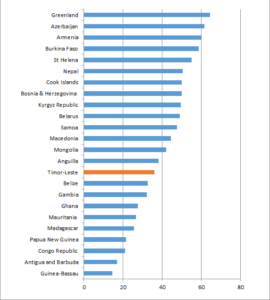

There are numerous corruption perception indices. They provide an outsider’s impression of the prevalence of corruption across the various branches of government. Some indices focus on issues of bribery, others are more general in scope. Some indices aim to engage with the general public, and others with businesses or NGOs. Perception indices can incentivise governments to tackle corruption given the reputational damage that they can inflict.

The shortcomings of perception indices, however, have been widely recognised, including in recent studies by UNDP and the IMF[2]. Their evidential base is limited; survey samples are generally small; within the same index a variety of methodologies may apply so they can lack internal consistency; methodologies change so trends can be questionable; standardisation is difficult to achieve between or even within countries and, as a result, the ranking of countries can vary from one perception index to another.

The relevance of objective data

Those agencies and officials responsible for preparing these indices are aware of the deficiencies and make considerable efforts to mitigate them. Their key deficiencies are unassailable, however. Perception indices are based on impression, personal experience and hearsay rather than hard fact. In a multi-faceted study of villagers’ perceptions of corruption affecting road building in Indonesia, Olken finds that perceptions are a good indicator of the presence but not the quantum of corruption. He concludes that “there is little alternative to continuing to collect more objective measures of corruption, difficult though that may be”[3]. These factors can allow governments to diminish the importance of the messages that perception surveys contain.

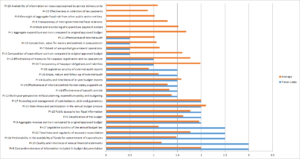

An alternative approach has been proposed in a recent paper by Fazekas[4]. The paper gives an account of recent research into public procurement in which legal, regulatory and administrative records have been analysed to reveal the presence of corruption. Relevant factors include: the characteristics of the tendering process; the political affiliations and personal connections of suppliers; and the location and transparency of information about the ownership of these supplier companies. Fazekas correlates these various data sets to reveal behaviour that indicates a skewing of contract awards toward suppliers with particular characteristics.

Fazekas uses the term ‘objective’ to refer to factual data that are not mediated by stakeholders’ perceptions, judgments, or self-reported experiences. Nevertheless, the data are based on provable characteristics (e.g., from suppliers and procurement agencies). This approach, however, can provide some significant challenges. Databases may not be available electronically, thus hampering data collection, and information is not collected on a systematic basis across countries. Despite these reservations, the approach can produce valuable evidence identifying areas of public administration that are especially prone to corruption, the role of officials in facilitating corruption, and the means by which corruption is being perpetrated.

Objective data analysis and developing countries

European countries and the USA have been at the forefront of this kind of work, but it also has potential for guiding administrative scrutiny and reform in developing countries. The necessary analysis could be undertaken by internal auditors, anti-corruption agencies, or other oversight bodies. These agencies could use the results to improve system design, and commission detailed forensic investigations of those concerned.

Fazekas uses sophisticated statistical techniques, but simpler methods could also be employed to measure inappropriate administrative processes, potentially illicit flow of funds between parties with close personal ties, the unexplained accumulation of personal wealth, citizens’ complaints, and other indicators of corruption. These results could then be used to identify potential levels and sources of corruption and, if acted on, lend credence to the government’s anti-corruption commitments.

The approach outlined above is relevant to national and local government, as well as public corporations where significant levels of corruption can occur at the highest levels. Such work could be enhanced through external moderation and research collaboration across national boundaries, perhaps at regional level. A recent piece by the present author, published here, discusses the growing relevance of digital media to governance reform.

The importance of national leadership

Objective data analysis can offer a clearer insight into the systemic nature of corrupt behaviour, thus providing a more precise indication of the corrupt parts of an administration, the number of external parties that are engaged in corruption, and features of the PFM system that need to be strengthened. It can provide data to support a vigilant administration that wishes to maintain pressure on corruption, complementing efforts to increase prosecutions or administrative reforms.

Whatever ideas are advanced, they will all require commitment from national leaders if they are to succeed.

[1] David Fellows is Co-principal of PFMConnect. He is an accountant and PFM specialist with significant interests in digital service development and performance management. His thanks are extended to Cornelia Körtl and Domenico Polloni for their invaluable contribution to this article.

[2] UNDPs Guide to Measuring Corruption and Anti-Corruption (2015). See also IMF 2017, “The Role of the Fund in Governance Issues – Review of the Guidance Note, Preliminary Considerations”.

[3] Benjamin A Olken, “Corruption Perceptions vs Reality” – https://economics.mit.edu/files/3931

[4] Mihály Fazekas “A Comprehensive Review of Objective Corruption Proxies in Public Procurement” https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2891017.

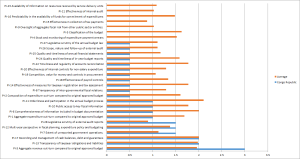

Download a pdf version of Figure 2

Download a pdf version of Figure 2