Corruption in East Africa (a US perspective)

Introduction

The United States State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices (“country reports”) strive to provide a factual and objective record on the status of human rights worldwide. The 2021 country reports were published on 12 April 2022.

Section 4 of the country reports provides an assessment of Corruption and Lack of Transparency in Government which addresses the extent to which a country’s law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials and the level of implementation of these laws.

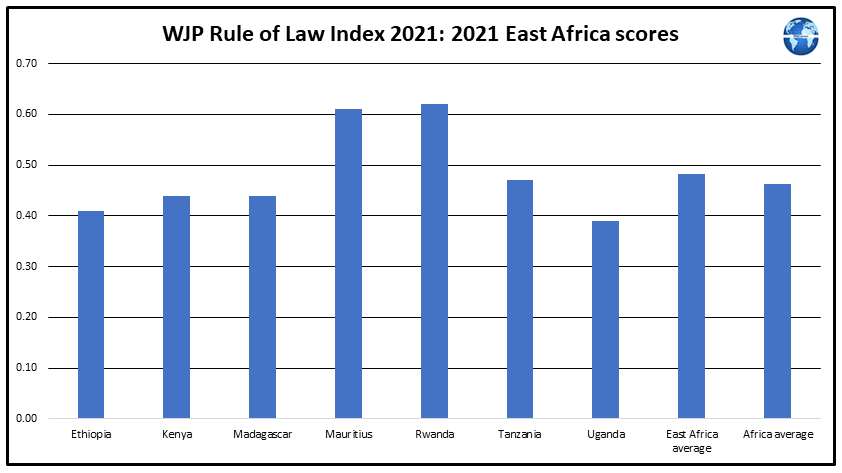

Scores for East African countries published by Transparency International in their 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) report demonstrate that East Africa was ranked second out of the five African regions in terms of improvements in CPI scores during 2012-2021. Individual country CPI score performance was mixed for East African countries in the 2012-2021 period. The country reports for East African countries reveal that only two East African countries were effectively implementing current criminal penalties for corruption by officials. Further discussion on corruption trends in East African countries is provided here.

Details of the overview comments for East African countries in the 2021 country reports are provided below.

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively, and officials frequently engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. There were numerous reports of government corruption.

The National Commission for Preventing and Fighting Corruption was an independent administrative authority established to combat corruption, including through education and mobilization of the public. In 2016 the president repealed the provisions of the law that created the commission, citing its failure to produce any results. The Constitutional Court subsequently invalidated this decision, noting that a presidential decree may not overturn a law. Nevertheless, the president has neither renewed the commissioners’ mandates nor appointed replacement members.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for official corruption, but the government did not implement the law effectively, and officials often engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. According to the World Bank’s most recent Worldwide Governance Indicators, government corruption was a serious problem.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively. Officials sometimes engaged in corrupt practices with impunity.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for conviction of corruption. The government did not implement the law effectively or comprehensively. The government enacted policies to hold government officials more accountable. There were isolated reports of government corruption. Officials sometimes engaged in corrupt practices with impunity.

On February 19, the HOPR issued the revised proclamation for the establishment of the Federal Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission, which assessed that the revised proclamation would increase its capacity to implement the law. “

“The law provides criminal penalties for official corruption. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year. Officials frequently engaged in allegedly corrupt practices with impunity. Despite public progress in fighting corruption, the government continued to face hurdles in implementing relevant laws effectively. The slow processing of corruption cases was exacerbated by COVID-19 containment measures, with courts lacking sufficient technological capacity to hear cases remotely.”

“The law provides for criminal penalties for official corruption, but the government did not implement the law effectively. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively, and officials sometimes engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. There were isolated reports of government corruption during the year.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for conviction of corruption by officials and private persons transacting business with the government that include imprisonment and fines, and the government generally implemented the law effectively. There were isolated reports of government corruption during the year, particularly related to road construction projects. The law also provides for citizens who report requests for bribes by government officials to receive financial rewards when officials are prosecuted and convicted.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for conviction of corruption by officials, and the government implemented the law effectively. There were isolated reports of government corruption during the year.”

“The law provides for criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not effectively implement the law. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year.”

“The transitional constitution provides for criminal penalties for acts of corruption by officials. The government did not implement the law. Poor recordkeeping, lax accounting procedures, absence of adherence to procurement laws, and a lack of accountability and corrective legislation compounded the problem. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, and the government did not implement the law effectively. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively. There were isolated reports of government corruption during the year. President Hassan took several steps to signal a commitment to fighting corruption. These included surprise inspections of ministries, hospitals, and the port of Dar es Salaam, often followed by the immediate dismissal or suspension of officials.”

“The law provides criminal penalties of up to 12 years’ imprisonment and confiscation of the convicted persons’ property for official corruption.

Nevertheless, transparency civil society organizations stated the government did not implement the law effectively, and there were numerous reports of government corruption during the year. Officials frequently engaged in corrupt practices with impunity, and many corruption cases remained pending for years.”

Conclusion

The country reports for East African countries demonstrate that only a small proportion of these countries are well placed to fight against corruption by officials.

Progress in combatting public sector corruption in East Africa is likely to be modest while the relevant authorities fail to enforce criminal penalties for corruption.