Introduction

The United States State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices (“country reports”) strive to provide a factual and objective record on the status of human rights worldwide. The 2021 country reports were published on 12 April 2022.

Section 4 of the country reports provides an assessment of Corruption and Lack of Transparency in Government which addresses the extent to which a country’s law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials and the level of implementation of these laws.

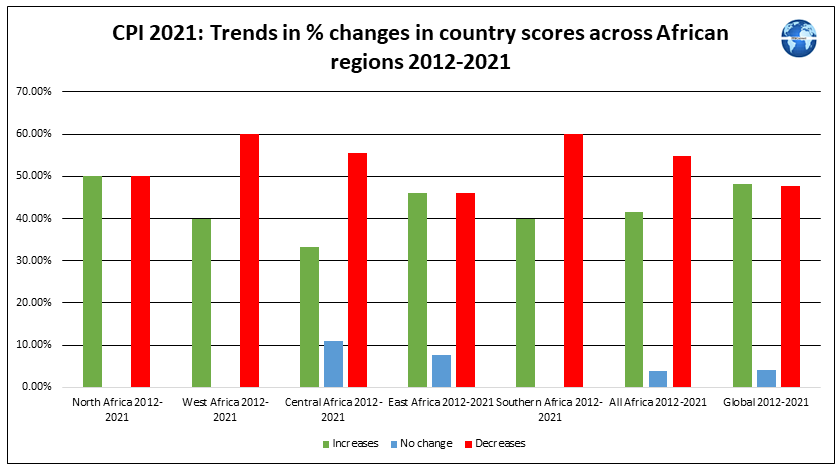

Scores for Commonwealth Africa countries published by Transparency International in their 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) report demonstrate that the majority of the nineteen Commonwealth Africa countries failed to increase their 2012 CPI scores during 2012-2021. The weaknesses in the implementation of criminal penalties for corruption by officials have no doubt contributed in some way to the lack of progress in addressing corruption in a number of Commonwealth Africa countries. Further discussion on corruption trends in Commonwealth Africa countries is provided here.

Details of the overview comments for Commonwealth Africa countries in the 2021 country reports are provided below.

Botswana

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, and the government generally sought to implement these laws effectively. Officials tasked with enforcement lacked adequate training and resources, however. Media reports of government corruption continued. During the year there were numerous reports of government corruption, including allegations tied to tenders issued by local governments for COVID-19 projects, such as renovating public facilities so that they complied with virus prevention measures, as well as in the acquisition of personal protective equipment. A 2019 poll by Transparency International found that 7 percent of those polled had paid bribes to government officials, an increase from the 1 percent who reported paying bribes in a 2015 poll.”

Cameroon

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively. There were numerous reports of government corruption. Officials sometimes engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. The law identifies different offenses as corruption, including influence peddling, involvement in a prohibited employment, and failure to declare a known conflict of interest. Reporting corruption was encouraged through exempting whistleblowers from criminal proceedings. In addition to the laws, the National Anticorruption Agency (CONAC), Special Criminal Court, National Financial Investigation Agency, Ministry in Charge of Supreme State Audit, and Audit Bench of the Supreme Court also contributed to fighting corruption in the country. CONAC, the most prominent of the anticorruption agencies, was constrained by the absence of any legislative or presidential mandate that could empower it to combat corruption. There were reports that senior officials sentenced to prison were not always required to forfeit their ill-gotten gains.”

Eswatini

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, and the government generally implemented the law effectively. There were isolated reports of government corruption during the year. Officials sometimes engaged in corrupt practices with impunity.”

Gambia

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not credibly investigate or prosecute any official accused of corruption. There were many allegations of government corruption.”

Ghana

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by government officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively, and officials frequently engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. There were numerous reports of government corruption. Corruption was present in all branches of government, according to media and NGOs, including recruitment into the security services. Since the first special prosecutor took office in 2018, no corruption case undertaken by that office resulted in a conviction. When the new special prosecutor took office in August, his staff included one investigator and one prosecutor, both seconded from other offices.

The government took steps to implement laws intended to foster more transparency and accountability in public affairs. In July 2020 authorities commissioned the Right to Information (RTI) secretariat to provide support to RTI personnel in the public sector; however, some civil society organizations stated the government had not made sufficient progress implementing the law.

The country continued use of the national anticorruption online reporting dashboard, for the coordination of all anticorruption efforts of various governmental bodies.”

Kenya

“The law provides criminal penalties for official corruption. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year. Officials frequently engaged in allegedly corrupt practices with impunity. Despite public progress in fighting corruption, the government continued to face hurdles in implementing relevant laws effectively. The slow processing of corruption cases was exacerbated by COVID-19 containment measures, with courts lacking sufficient technological capacity to hear cases remotely.”

Lesotho

“The law provides criminal penalties for conviction of corruption by officials. The government did not implement the law effectively, and some officials engaged in corrupt practices with impunity.”

Malawi

“The law provides criminal penalties for conviction of corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively. Officials sometimes engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year.

The government, in cooperation with donors, continued implementation of an action plan to pursue cases of corruption, reviewed how the “Cashgate” corruption scandal occurred, and introduced internal controls and improved systems to prevent further occurrences. Progress on investigations and promised reforms was slow.”

Mauritius

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively, and officials sometimes engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. There were isolated reports of government corruption during the year.”

Mozambique

“The law provides criminal penalties for conviction of corrupt acts by officials; however, the government did not implement the law effectively, and officials often engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. There were numerous reports of corruption in all branches and at all levels of government during the year.”

Namibia

“The law provides criminal penalties for conviction of official corruption; however, the government did not implement the law effectively. Officials sometimes engaged in corrupt practices with impunity.”

Nigeria

“Although the law provides criminal penalties for conviction of official corruption, the government did not consistently implement the law, and government employees, including elected officials, frequently engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. Massive, widespread, and pervasive corruption affected all levels of government, including the judiciary and security services. The constitution provides immunity from civil and criminal prosecution for the president, vice president, governors, and deputy governors while in office. There were numerous allegations of government corruption during the year.”

Rwanda

“The law provides criminal penalties for conviction of corruption by officials and private persons transacting business with the government that include imprisonment and fines, and the government generally implemented the law effectively. There were isolated reports of government corruption during the year, particularly related to road construction projects. The law also provides for citizens who report requests for bribes by government officials to receive financial rewards when officials are prosecuted and convicted.”

Seychelles

“The law provides criminal penalties for conviction of corruption by officials, and the government implemented the law effectively. There were isolated reports of government corruption during the year.”

Sierra Leone

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, and the government generally implemented the law effectively. There were numerous reports of government corruption.”

South Africa

“The law provides for criminal penalties for conviction of official corruption, and the government generally did not implement the law effectively, and officials sometimes engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year.”

Tanzania

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively. There were isolated reports of government corruption during the year. President Hassan took several steps to signal a commitment to fighting corruption. These included surprise inspections of ministries, hospitals, and the port of Dar es Salaam, often followed by the immediate dismissal or suspension of officials.”

Uganda

“The law provides criminal penalties of up to 12 years’ imprisonment and confiscation of the convicted persons’ property for official corruption.

Nevertheless, transparency civil society organizations stated the government did not implement the law effectively, and there were numerous reports of government corruption during the year. Officials frequently engaged in corrupt practices with impunity, and many corruption cases remained pending for years.”

Zambia

“The law provides criminal penalties for officials convicted of corruption, and the government attempted to enforce the law but did so inconsistently. Officials often engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. Although the government collaborated with the international community and civil society organizations to improve capacity to investigate and prevent corruption, anticorruption NGOs observed that, the enforcement rate was low among senior government officials and in the civil service.

According to Transparency International Zambia, the conviction rate for those prosecuted for corruption was 10 to 20 percent. The Patriotic Front government did not effectively or consistently apply laws against corrupt officials; it selectively applied anticorruption law to target opposition leaders or officials who ran afoul of it. Transparency International Zambia further reported that, during the Patriotic Front administration, officials frequently engaged in corrupt practices with impunity.”

Conclusion

The United States State Department has assessed that more than half of Commonwealth Africa countries are not effectively implementing penalties for corrupt activities. This outcome is similar to the prevailing overall trend in CPI scores reported for 2012-2021.

Considerable effort is required by Commonwealth Africa countries and their development partners in the short to medium term to reverse the current unsatisfactory trend in implementation of penalties for corrupt activities.