Coherent Policy, Planning, and Performance for Delivering the SDGs

Posted by David Fellows[1]

This is an extraordinarily important time for coherent policy, planning, and performance – the “3 Ps” – for delivering the SDGs and other core public policy objectives.

The SDGs present an extensive range of essential service improvements that are applicable across the world. The threat posed by climate change has become a major international issue with immensely ambitious remedial targets and huge spending requirements. Governments are also under pressure to introduce gender responsive budgeting and digitalize their public finances, reforms that offer huge benefits but also challenges and costs in the short to medium-term. At the same time, the Covid-19 pandemic has devastated many economies and produced huge fiscal burdens, increasing the challenge of delivering the SDGs and better environmental outcomes.

A coherent delivery framework

It is important that governments take decisions within a strategic framework that represents an appropriate timeframe and deals clearly with policy goals, service responses, resources deployed, and outcomes achieved. The various elements of this framework include:

- A vision having a 10-year perspective expressed in terms of outcomes.

- Objectives set with a 3-5 year delivery time frame, consistent with achieving the vision.

- Delivery targets for each of the next 3-5 years in terms of service outputs relevant to the performance outcomes.

- 3-5 year budgets for agencies or programs that reflect the delivery outcomes and performance targets that each budget represents.

- Annual accounts that set out executive responsibilities, annual performance outcome and delivery targets and the actual performance achieved.

- Training and recruitment plans that enable public agencies to operate the systems and deliver the services that have been approved.

Delivering change

Successful reform is an elusive concept. Any initiative worth doing must have a benefits realisation plan specifying the steps necessary to ensure that progress is being made and that the end results are achieved.

Services and changes to service provision should be protected by risk management strategies that seek to mitigate internal or external events and shocks that may otherwise hamper delivery or destroy valuable assets.

Review and accountability

The various elements of the framework must be consistent with each other. When major new commitments are proposed, or it becomes obvious that major targets are no longer achievable then a review of the framework should be undertaken. In addition, there should be an annual review of the framework as part of the annual budget preparation process, perhaps as part of a wider spending review. Policies, plans, performance, and the results of review processes should be made public. There is no aspect of the planning and delivery process that cannot benefit from public scrutiny and comment. It is the responsibility of all public institutions in a democratic country to make themselves open and responsive to such a dialogue.

The PFM challenge for developing countries

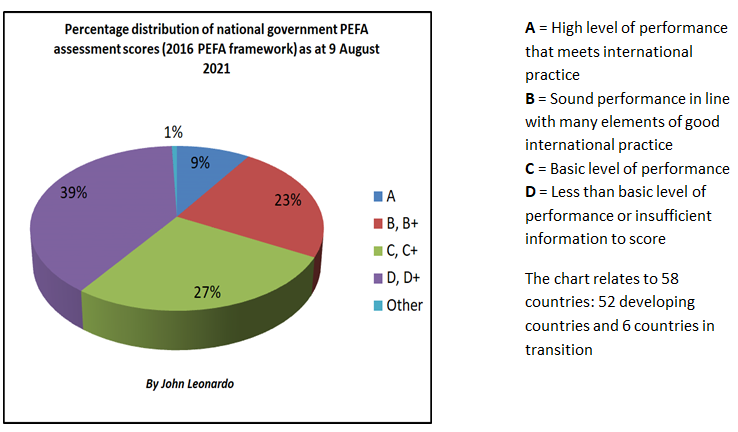

The relatively poor condition of PFM in developing countries shown in the chart suggests the difficulties that developing countries face in planning, managing, and maintaining their existing budget systems. The SDGs and other global pressures to increase spending represent additional challenges for PFM systems to face. Multilateral decisions on the SDGs and climate change must therefore take account of the consequences for developing nations given the likely dependence of successful outcomes on their cooperation.

Conclusion

The immense pressures on governments worldwide to fulfil the global obligations and pressures described above often require concerted action. If governments are to succeed without making over-extended commitments, wasting time and money on impractical solutions, they must make decisions within the rigours of a fully operational policy, planning, and performance framework. Multilateral agreements, economic, social and technological considerations will all feed into framework construction but the integrity of the framework is key.

Framework development will inevitably present hard choices but that is a strength of the process. It should also provide a coherent basis for democratic accountability if, as a result, drastic life changes are required, freedoms are curtailed, and personal costs are increased.

This article was first published by the International Monetary Fund’s Public Financial Management Blog on 20 September 2021.

[1] David Fellows began his career in UK local government where he became President of the Society of Municipal Treasurers and a pioneer of digital government. He followed this with appointments in the UK Cabinet Office and the National Treasury of South Africa. He is a Director of PFMConnect.