Levelling-up White Paper commentary: Time to deliver

By David Fellows

The WP sets out a decade long programme of UK public service development for the whole of the UK. It is presented under four headings:

- Empowering Local Leaders and Communities (extending combined authorities and mayoral capacity to secure local economic and physical improvement)

- Improving Productivity, Pay, Jobs and Living Standards (promoting innovation and growth in areas of low productivity and limited job opportunities including new institutes of technology, upgrading local transport and road maintenance)

- Spreading Opportunities and Improving Public Services (school, hospital and institutes of technology developments)

- Restoring Local Pride (home energy improvement schemes, community development and neighbourhood appearance)

The WP makes clear that funding for these activities, some of which are already in progress, is to be delivered through 26 different funding mechanisms (some references imply there may be more).

It has been argued that the need for levelling-up is based on a post-war bias in public funding toward London and the South East reaching up to Oxford and Cambridge. This geography is variously referred to as ‘The Golden Triangle’ or ‘The Greater South East’. I and others have remarked on this bias over the past few years, including the right of centre think tank ‘Onward’ that has produced a series of very useful studies. There can be little doubt that the Golden Triangle has received project funding from Government on less demanding standards than has been applied elsewhere and on a very regular basis. It is clear that the quantum of funding awarded to this area, augmented by its frequent selection as the preferred location for flagship initiatives, could not have failed to provide it with an enviable diversity of employment, huge economic impetus, and considerable prosperity compared to that of the outlying regions.

I would argue that over the past 30 years it became accepted thinking that the scientific, medical, technological and financial service developments within The Golden Triangle would carry the rest of the country and that the regions were heading towards inevitable decline. The banking crisis of 2007-8 may have accelerated this situation but I suggest that this assumption was implicit decades earlier. The apprenticeship programmes and regional development initiatives that were launched in this period had neither the funding, the richness of concept nor the facilitating heft to do much more than provide token comfort despite the best efforts of some ministers involved.

The WP demonstrates that UK regions outside the Golden Triangle have below average gross disposable income and productivity levels compared to the UK as a whole. In addition, the UK’s second-tier cities lag both other countries’ second-tier cities, and the UK’s national average, suggesting a significant under-performance to their potential.

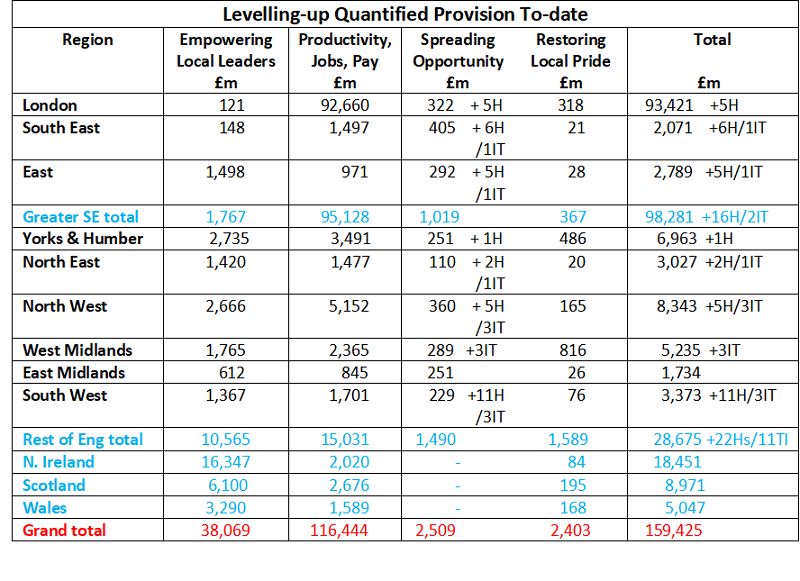

Strikingly the WP not only demonstrates that the Golden Triangle has been afforded a huge economic advantage over the rest of the UK but that this is so baked-in that massive infrastructure developments currently in train will ensure that this advantage inevitably increases over the next decade. Despite the levelling -up funding earmarked for the regions the WP indicates that during this period on current standing London will receive 58% of the UK’s development funding, with the Golden Triangle receiving over 61% in total. In summary, the reported sums are, as follows:

It is clearly time to address the psychological, financial, economic and social imbalance that are so detrimental to regional communities and at the same time have consequences that place a huge strain on ordinary people trying to live their lives within The Golden Triangle, particularly London.

Some particularly welcome features of the proposals

I welcome the decade long timeframe adopted in the WP although several decades will probably be required to evidence sustainable improvements. I also applaud the commitment to adopting a rigorous approach to performance measurement and transparency that will test the delivery and effectiveness of the programme and help create a system of accountability. This task must be seen as the starting point for a process of continuous learning and improvement.

Overall the WP provides an astonishingly honest account of the need for fundamental change to the way the UK perceives itself politically, economically and administratively. A cohesive alignment of special talent at political and administrative levels is now required to take advantage of this impressive start.

A generally supportive approach by the commentariat would extremely helpful but the Government should assume that it must bear the weight of public messaging to build understanding and participation a development process that is bound to have both highlights and disappointments.

Some suggestions

There are many aspects of the WP that seem to demand refinement and in some cases radical revision, as would be expected given the extensive nature of the Government’s vision, including:

- Setting the scene. There is some bewilderment expressed in the opening chapter of the WP as to how the UK came to experience such powerful and persistent disparities between areas of the country compared to experiences elsewhere. In places there tends to be an argument that these disparities are equally felt across the UK, including London. Frankly, I can only attribute London’s internal disparities to an astonishing failure of sophistication by those responsible for guiding the immense power of the London economy. I feel that the professed astonishment should have been at least partly mitigated by an explanation of the bias in public policy and that has favoured the Golden Triangle for so long. This acknowledgement can be inferred but should be more evident.

It is important for society at large, politicians (national and local) and civil servants to understand that past preferment must cease, that a line has been drawn.

- Digestibility. There appears to be considerable overlap between the four programme aspects and given that the coverage of the overall programme is so extensive there is a good case for dividing it operationally into two distinct segments.

- Driving regional business growth through: innovation and product development leading to improved productivity and business expansion; improved communication, and shared learning within the business community; more extensive linkages between the business community, universities and other relevant institutions (existing and new); and closer working between Government, local government and other business support organisations (see my previous paper on these issues[1]); and

- Providing a fairer distribution of public services reflecting other local needs and conditions throughout the UK. There will be inevitable overlaps between these two aspects of the WP not least relating to infrastructure but it is important to identify and design specific initiatives around the predominant drivers if public money is to be spent effectively and in a timely manner. It must also be understood that success in (1) will reduce the imbalances in health, social and environmental outcomes relevant to (2) and without success in (1) investment in (2) will be dissipated.

Transparency and review will undoubtedly raise many issues causing constant refinement to the approach and this is to be welcomed as and when it occurs.

- The funding programme nightmare. The WP demonstrates the confusion of funding sources that besets any attempt to make change across a broad, interrelated swathe of UK public service. In theory the approach places all funding proposals for the whole country on a level playing field but we know that the level playing field is warped and ignored at will. It is a system by which administrators play a game which only they can ever hope to understand and importantly it acts as a protection against criticism of their decisions. What really needs attention are the outcomes and the way in which performance targets are set. The more complex the system the less honest the results. Adopt simpler, more flexible funding mechanisms with clearer performance metrics and an emphasis on the often forgotten outcomes.

- A democratic sea change. The prominence given to executive mayors tends more to a sea change than a refinement. At present elected mayors and city regions have limited powers with mayors acting as local convenors. The WP proposes some significant additional funding being available that should assist their powers of persuasion (depending on the fine details of the ‘Empowering Leaders’ funding). It is, however, interesting that levelling-up discussion is usually conducted in the context of regional development, as reflected in the WP summary but the detail on the ground and in the Empowerment section concern much smaller areas.

Surely a regional view is a more practical proposition. Does not the fragmentation of the regions for the purpose of economic development make them more obscure and complex to business, therefore, less inviting? Is this not why the Northern Power House and West Midlands engine were given such extensive catchment areas?

Post-war local government reform has been a nightmare and further attempts to impose nation-wide change is probably a step too far but regional mayors with extensive executive powers directed at economic regeneration could be highly beneficial to this agenda. They could work in collaboration with a system of local consultative councils that also had responsibility for community services. This would fit more the direction of travel than the current complexity of personnel, titles, powers and local exceptions. It would make the regions more comparable in scale to London and offer a simpler local structure on which the interactions between so many different parties must take place if this vital project it to be successful.

- Departmentalism. A similar point could be made about the civil service. Its model is pre-war, virtually nineteen century, when individual departments maintained a near independent existence. Neither the Cabinet Office nor No 10 is really in charge. Combining these two central vehicles seems essential but it does not mean that they will necessarily have more coordinating power or have more rights of accountability over departments. The WP brilliantly shows the interconnectedness of a visionary, transformative programme. What it really needs is a civil service that can be coordinated and held to account internally in a managerial sense. It also needs ministers that are not temporary post-holders but seasoned political leaders in their field, expected to serve a full parliamentary term and perhaps longer, who can become properly acquainted with their brief, their department and those in the wider world with whom their department does business.

- Central meets local. It is clear that local politicians want local control. Which politician doesn’t want power you might say? But central politicians want local control too, why is this? Locals do know the lay of the land, have planning responsibilities and lots of people on the ground who provide useful support services. Even so, Government holds many of the cards, including special tax and loan schemes, huge Government spending programmes (both routine and research), better control over the shape of higher and further education than local decision-takers, primacy over regulation (and deregulation) and more influence over inward investment. Is the Government hedging against failure or does it assume that funding mechanisms and behind the scenes arm twisting will provide control without responsibility? The game as proposed is too big to be so coy.

There needs to be a more thorough discussion of what the Government will bring to the table and how it will be involved given the enormity of the proposition. Regional directors will simply not cut it for this scale of programming. For a programme of this complexity a minister and official of deputy permanent secretary level needs to be assigned to each region however the programmes are to be configured. They would work with regional leaders, use their clout inside Government and Whitehall and work in tandem with local politicians on deals with major business partners. This takes into account that business investors may need to be convinced that local and central decision-takers are united in their ambition and evidently willing to work together over the long-term with mutual respect. More needs to be said on this in the next stage.

- The private sector invitation. Apart from seeking general private sector responses to the WP it could be helpful to invite thoughts on the feasibility of some specific issues: the deepening of business to business collaboration; the development of interrelated areas of expertise whether on a national or local basis; the development of local supply chains for specific products; and opportunities for the creation or advancement of distinctive regional business specialisms. Also thoughts on the means by which closer working relationships could be developed between business and the education sector including institutes of technology, further education colleges and university departments in order to drive innovation and knowledge transfer and the likely benefits from proposed changes. Specific comments could also be invited on new or improved ways in which the wider public sector could help facilitate such developments.

- The London plan. There needs to be a plan for aligning the development of the Golden Triangle with the development model for the regions to facilitate a viable public spending space and a more balance growth model. The pandemic increased the practice of home working but initial signs of this practice were evident in London long before. Nevertheless its acceleration has caused havoc to the business models of public and private service providers. This time consequences must be thought through. The social return, particularly to London, must be tangible and properly planned with any detrimental factors identified and mitigated wherever possible. To deny the need for this requirement is to deny the intention to succeed.

Final thoughts

Is there really a need to do something this radical? In a sense the genie escaped the bottle at the last election when the memorable ‘levelling-up’ term was widely used to such good effect. The term cristalised the insistent need for change in the regions.

The possibility of diluting the concept must be tempting. There is no blueprint for success. Parallels with reforms in other countries can be drawn but practice is rarely transferrable at scale although lessons must always be sought and applied where possible. Beneficiaries of past preferment will inevitably express misgivings at the loss of their special place in Government affections and some will mount outright opposition to meaningful change.

Even so, this massive initiative is both necessary and appropriate to the present time, particularly in the context of the need to achieve post-pandemic renewal, demonstrate the full advantages of Brexit and deliver manifesto pledges. So the case for change can nolonger be evaded. The programme must now be explained, developed, defended and executed with irresistible determination.

Since this was first written there have been two changes of PM. The current PM’s position on this putative agenda is by no means clear. I suggest that there would be an immense feeling of betrayal in the regions if a decision was taken to effectively downplay the prospect of regional change that has been created and a return to an economic model based on the greater South East. It could be seen as the denial of nationhood by the Conservative Party. The jury is out and the signs do not look encouraging.

David Fellows is an accountant and early innovator in digital public service delivery. He worked extensively in UK local government, was a leader in the use of digital communication in UK public service and led a major EU project supporting the use of digital technology by regional SMEs. He became an advisor on local government reform in the UK Cabinet Office and an international advisor to the South African National Treasury. He is a director of PFMConnect, a public financial management and digital communication consultancy: david.fellows@pfmconnect.com

[1] https://blog-pfmconnect.com/levelling-up-opportunity-for-future-generations/