Levelling up opportunity – redressing social and economic disparities in the UK

By David Fellows (1)

This is an extraordinary time for the country and the Government. Despite the terrible consequences of Covid-19 and the challenges of Brexit, this is also a time that bears the seeds of a renaissance. Our new found freedoms, new ways of working and new sense of shared responsibility provide the means to redefine Great Britain for the 21st century.

Well before the Covid-19 struck digital technology had introduced new forms of remote working, shopping and entertainment but the virus has accelerated adoption. Greater flexibility of work location has been established and physical proximity to London is no longer the advantage it once was. This has improved the feasibility of ‘levelling up’ the regions, a commitment made by the PM on taking office. Levelling up also carries the potential to reduce pressure on accommodation in the London area and alleviate the worst of the capital’s housing crisis. With a little imagination levelling up could be seen as a win win prospect for the whole country.

Levelling up commitments

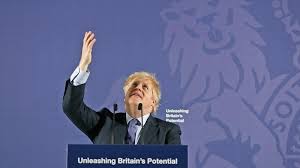

Recovery is always an aspirational project and we have a PM who epitomises this quality. His early call to use levelling up as the route to recovery from Covid-19 captured the public mood and certainly chimed with the expectations of Red Wall voters.

The Conservative manifesto for the 2019 election commits to ‘agenda for levelling up every part of Britain, investing in our great towns and cities, as well as rural and coastal areas’. Under the heading ‘Levelling up’ the March 2020 Budget asserts to need to ‘raise productivity and growth in all nations and regions for everyone, addressing disparities in economic and social outcomes’.

Regional disadvantage

The regions are suffering from long-term underperforming economies giving rise to the steady destruction of social structures as young professionals and skilled workers drift to the London area. This regional situation is to be contrasted with London where the City and Central Government directly and indirectly provide huge economic impetus. The concentration of media, major cultural venues, law courts, international tourism and a host of vastly resourced academic institutions add enormous weight.

This constitutes a system of self-serving parochialism that produces a continuous flow of advocacy for endless public and private sector investment. The thought of major institutions locating outside London has become almost risible. Some suggest that there is a spill-over effect from London to the regions but where this happens it consists of low-paid back-office jobs, call centres and branch plants that can be axed or offshored at a moment’s notice.

Levelling up challenge

It is worth considering the concept of levelling up in terms of the current socio-economic challenges facing the country and the regions: the attenuated international supply chains; overly heavy dependence on manufactures from across the world; the steady drain on young talent from the regions to London leaving behind increasingly vulnerable communities; the narrowing of employment opportunities in the regions that fit the skill sets, interests and monetary ambitions of regional communities; and the stagnant regional economies that require regular, and often resented support, from the national exchequer.

It is astounding to reflect that the UK has proportionately the smallest manufacturing sector of any OECD country (Gudgin & Coutts 2015 – see Bickerton below). In terms of shared prosperity a recent House of Commons briefing paper gives the GDP per head for the devolved administrations and English regions. The astonishing fact emerges that London’s value is £54,700; the South East £34,100; and the remainder are below the national average, mainly in the range £30,100 to 25,900 with the exception of the North East £23,600 & Wales £23,900. It is a crude but interesting comparison.

Apart from the extremely wealthy, London too has its problems. The housing crisis is borne of excessive demand compounded by a dysfunctional housing sector, an overly restrictive spatial planning system and political inertia. It is also worth considering the cost of continuing to develop the already congested and expensive London infrastructure. It has taken Covid-19 to emphasise the inherent risk entailed by an enormous concentration of cost and livelihoods invested in a London area public transport system that is reliant on a huge passenger throughput. The changing demand habits of the travelling public have shown the inbuilt risks to this system.

These factors suggest the potential benefits of rebalancing in favour of regional economies. This could include some reshoring of production, strengthening internal regional markets and developing the capacity to recognise and exploit regional economic potential.

For instance, there may be particular local relevance to the development of renewable energy technologies and support services; battery technology; high insulation house fabrication industries; and digital technology applications supported by local graduates from higher education (perhaps helping to develop local businesses). More specifically, computer aided design expertise offers support for improvements in the efficiency of manufacturing and agricultural processes that may help to offset the potentially higher costs of repatriated production and smaller companies may be prepared to collaborate in the creation of local skill sets required by emerging local industries.

The levelling up offer

As yet there is no clear indication from Government about the objectives, details or total spending commitment to be attached to the levelling up commitment. Colin and Carole Talbot in their paper ‘On the level’ considered the feasibility of interpreting the concept in terms of increasing regional public spending per capita to that of the capital. They concluded that a 6% rise in public spending would be required. In his thought-provoking paper ‘Brexit and the British growth model’ Christopher Bickerton traces the breakdown of the British socio-economic compact and asserts the need for a new social settlement in Britain. This could be taken as the underlying subject matter of a levelling up agenda.

The March budget’s reference to levelling up as cited above itemises infrastructure spending of £650bn up to 2024-5 for roads, railways, communications, schools, hospitals and power networks across the UK. A close-ended infrastructure dominated commitment would clearly suit the Treasury control instincts but such investment alone is unlikely to make a significant dent in the problem.

In his recent speech to the Conservative Party conference the PM affirmed his intention ‘to spread opportunity more widely and fairly’. Perhaps levelling up opportunity this is where the answer lies. But what sort of opportunity? I suggest this refers to people having an appropriate choice of work giving them the chance to earn a good living in a satisfying social and physical environment. The work depends on the individual’s aspirations: something reasonable in terms of pay, security and interest. The environment clearly includes friends and neighbours, safe streets and pleasant surroundings.

Admittedly this is not graphically clear, it does not have a specific price tag, its interpretation will certainly change over time and it can never be ticked off the to-do-list. Refinement will embrace a greater diversity of employment, wider spread of earnings, higher proportion of national wealth and personal income for the regions. It is the ultimate political task of continuous engagement and interpretation with the voters judging the results. To a large extent, the environmental aspect requires familiar public services to be properly delivered but the economic aspect requires some radical new thinking. The approach must be much more diverse, agile and collaborative than hitherto.

Levelling up tools

The general election manifesto asserts the need to give the regions ‘more control of how that investment is made’ and ‘to trust people to make decisions that are right for them’. Does the PM really wish to succeed by devolving responsibility for ‘levelling-up’ to local judgement on the basis that locals know best? A cursory inspection of the project will quickly find that the game is not in regional hands.

It is essential that local authorities, local businesses, local universities, local FE colleges and a plethora of regional organisations are seriously engaged. Many will have a major stake in the delivery but any plan that does not require Government to play a pivotal role in shaping and delivery has, in my opinion, no significant capacity or ambition to move the dial towards regional regeneration. How are the various bodies to be engaged if not by Government? Are Government departments not to make a significant contribution in the fields of taxation incentives, the creation and oversight of an investment vehicle, new procurement regimes and simplification of regulatory systems? The distancing of Government from regeneration is the story of repeated failure.

So what measures might a more appropriate regional revival scheme look like? The levelling up agenda could include: the use of Government procurement to promote regional economies and help develop emerging businesses (Government taking the risk of awarding high value work to the latter); a system of enterprise zones and free ports with tax incentives for business to relocate and invest; deregulation to encourage enterprise; the creation of regional investment institutions (to make good the lack of commercial appetite for regional business ventures); the introduction of integrated regional government export advice centres; and a properly decentralised Civil Service. The Government is also the paymaster of the higher and further education sectors that have a substantial contribution to make and this must surely be designed into proposals.

Low interest rates make infrastructure a superficially attractive proposition but it must be justified in terms of its relative benefits within the entire spectrum of measures that are potentially available. Its importance must not be overrated.

This exercise is a massive and complex undertaking with diverse elements: local and national, private and public, established institutions and new ones. Government departments must be effectively engaged. Emerging businesses will require special attention. Local business services will need to be kept in touch. . Local business services will need to be kept in touch. There must be a learning system that develops knowledge of what works in what circumstances, how to roll out and revise. Predecessor programmes failed to offer a sufficiently comprehensive framework but are a starting point for such learning.

In reality this cannot mean that every town that has been hard hit by decades of decline will be comprehensively revived in these terms. It will be necessary to spread the effects of the employment regeneration into established towns that become new suburbs but with the arrival of remote working that distinction will become increasingly blurred.

A new regional geography

There is also a requirement, in my view, for the creation of large regional economic development areas to facilitate the process of regeneration. There may be a temptation to restrict attention to the midlands and the north but this will be rightly challenged by other regions facing neglect. For instance, there could be four such regions: the North from Cheshire to Cumbria and across to the east coast; the West Midlands from Shropshire to Wiltshire; the East from Lincolnshire to Suffolk; and the West from Cornwall to Wiltshire and possibly up to Gloucestershire and out to Hampshire.

These four regions would form a powerful arc around London and the South East. There would be no intention to redraw local government boundaries to achieve this. Each economic development region would be an amalgam of its various regional institutions. It would be designed to explore and refine the key development levers made available to it. It would provide the basis for the development of a country that is much more robust and interconnected than it is today.

Timescale

The displacement effects of Covid-19 and, to a lesser extent, Brexit are enormous. There is not the financial or organisational capacity to complete the levelling up process and other key Government commitments in the course of a single Parliament. This is a programme for the next decade. Nevertheless, this is the time to articulate the broad vision and present an outline programme of measures to give it effect. Early decisions must be taken on the first tranche of initiatives linked to the vision. Perhaps initial proposals for the current Parliament could be developed for announcement alongside the postponed autumn budget if this were scheduled for the spring.

The rumoured relocation of a substantial proportion of the Treasury to Leeds could offer evidence of intent for an extensive programme of departmental relocations. Such a programme would be more about a shift in departmental attention to the regions than the regionalisation of public spending.

Future domestic issues

Of course there are many other related issues requiring attention: NHS management and the reform of social care; the allocation of responsibilities within the state schooling system given the decreasing role of local education authorities; the modernisation of the Civil Service and Cabinet Government; the future role of the armed services; and devolution within the UK. All these issues and more are important to the nation’s development but they are inevitably subservient to the blue print for economic recovery and its key theme of levelling up opportunity.

Conclusion

In his recent speech to the Conservative Party conference the PM affirmed his intention ‘to spread opportunity more widely and fairly’. It could be said that ‘levelling up opportunity’ is his key commitment to the country.

If this is the task then measures taken by Government must go far beyond a programme of infrastructure development since that cannot begin to have the impact required. The real task requires Government to take a major role, contributing muscle and breadth of attack.

The concept of levelling up opportunity must now be supported by a clearly articulated vision and an outline of the mechanisms for delivery and subsequent refinement over the next decade. This must constitute a key element of the early post-Covid economic revival. There may never be a better chance to put this vision into effect.

(1) David Fellows has worked extensively in UK local government and in the Cabinet Office as an advisor on local government reform. He is a director of PFMConnect, a public financial management consultancy: david.fellows@pfmconnect.com

(2) A short video discussing the issues raised in this blog is available here.