Small Island Developing States, COVID-19 and Digital Technology

Posted by David Fellows[1]and John Leonardo[2]

The impact of COVID-19

COVID-19 has changed behaviour throughout the world and social distancing has been the key driver. Workers in factories, shops and offices have been protected by creating greater space between workstations, erecting protective screens and using protective clothing. Distancing requirements have been introduced in bars, cafes, restaurants, hotels, markets and shopping centres. All economies have suffered, especially the hospitality industry, air travel and public transport. Unemployment has soared. Schools and higher education colleges have closed. Many countries are turning to the IMF for support.

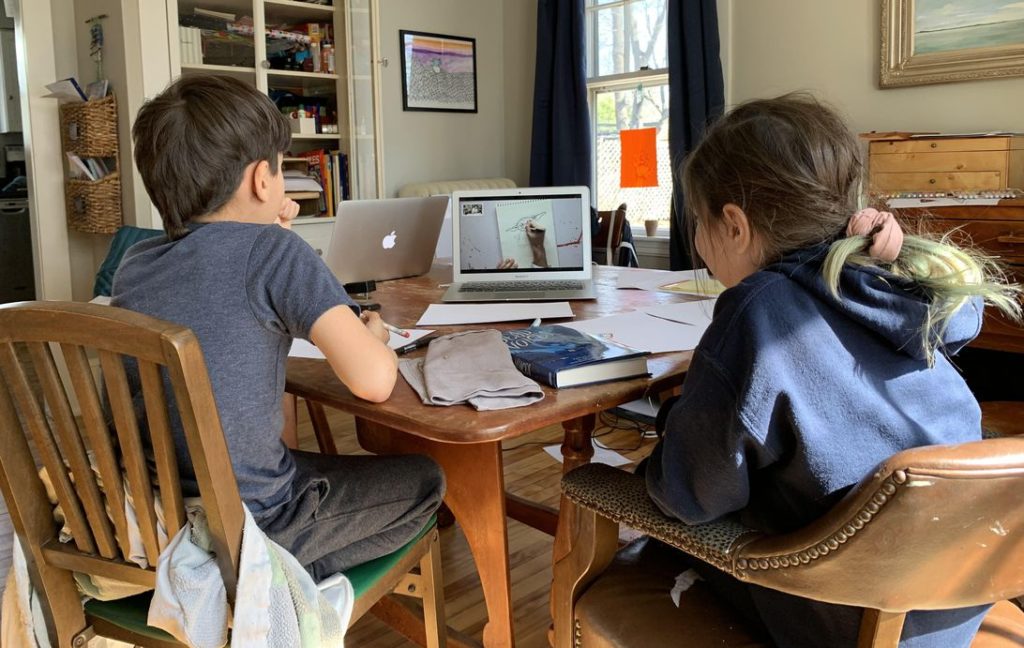

The internet has proved a beneficial facilitator of economic activity, allowing most administrative work and the ordering of goods and services to be undertaken at home. Video conferencing has facilitated meetings with colleagues, business partners and clients, and helped maintain contact with friends. Online learning has featured in reopening plans for higher education and some schools. In this new world digital technology has achieved an elevated significance beyond its already pervasive presence in the pre-COVID era. In some ways it has already established a new normal.

This brief piece focuses on small island developing states (SIDS) but even here the challenges are not identical. Some countries depend heavily on a now-dormant tourist industry and shoulder severe difficulties. These include poverty, remoteness, disbursed communities and the need to combat the threat of natural disasters. The virus demands a minimisation of personal contact for which the absence of good quality, low cost digital communication leaves many states poorly prepared. The UN E-Government Survey 2020 notes that of the SIDS only Singapore and Bahrain have high overall scores; almost half scored less than 50% of Singapore’s score for infrastructure.

Communication infrastructure

Good quality digital communication requires fibre-optic broadband cabling to support business use and homeworking with adequate resilience, even including 4G and Wi-Fi. 5G is costly and has potential shortcomings at present. This option requires specialist advice.

Understanding behaviour is important to government strategy. Contributing factors include levels of public education, affluence, user tariffs and local cost factors. Lobbying based on knowledge of the operational intentions of the marine cable-laying industry could be important.

Regional collaboration could provide impetus to network improvement strategies, regulatory frameworks and licensing agreements.

Technology applications

The digital service revolution discussed above and already taking place across the world, accelerated by the onset of COVID-19, is inescapably relevant to SIDS. There are many specific business applications of relevance to SIDS, including: health advice (including C-19) and personal consultations; agricultural monitoring and market information on crops and livestock; and weather monitoring for fishing, agriculture and general safety considerations. Additionally, expatriate monetary transfers are being undertaken increasingly using digital systems. The creation of digital services relevant to developing countries gathers pace and must be encouraged.

Video conferencing, email and document handling systems provide an essential communication layer that is particularly useful to achieve social distancing.

Apart from their use of major business applications governments can make use of social media for public messaging, for instance, demonstrating transparency and engaging citizens the struggle against corruption when resources are so scarce.

Technology skills

Digital communication infrastructure must be complemented by a capacity for: upgrading, expansion and rerouting of infrastructure; installing application software; implementing major software packages; and even the development of service applications. This requires learning at various levels gained from school, college, in-service courses and practical experience.

An understanding of the technology is also required to educate potential adopters about the possibilities that digital communication offers them. This includes the general public, small businesses, the public sector and larger private sector organisations.

Digital technology skill development is essential to help SIDS adjust to the current situation.

Towards cost-effective solutions

COVID-19 is forcing change to the way people live throughout the world and economies are in crisis. Digital communication offers the capacity for helping maintain business continuity. Most SIDS would benefit from a higher standard of affordable digital communication supporting improved digital service delivery.

Digital technology must be designed to the needs and circumstances of individual states. Nevertheless, there could be much to gain from cost-effective collaboration between SIDS for the purposes of sharing and developing:

(i) an understanding of the economic and social impact of COVID-19 and ways of mitigating these effects through digital communications;

(ii) market-shaping policies and practices for increasing the availability of digital communication at an affordable price;

(iii) strategies and programs to support the provision of expertise in digital technology and its use by business, public services and the general public; and

(iv) knowledge of relevant progress made on these issues throughout the world.

Such an initiative, whether on a global or regional basis, could include SIDS, development agencies, the digital service industry, other private sector partners and potentially the Commonwealth Small States Centre of Excellence. Is this a step too far?

This blog was published by the International Monetary Fund’s Public Financial Management Blog on 18 August 2020 at https://blog-pfm.imf.org/pfmblog/2020/08/-small-island-developing-states-covid-19-and-digital-technology-.html.

[1] David Fellows is an accountant who has worked extensively in UK local government, the Cabinet Office as an advisor on local government reform and as an international development PFM advisor. He was a leader in the application of digital communication to UK public sector service delivery. He is a director of PFMConnect, a public financial management consultancy: david.fellows@pfmconnect.com.

[2] John Leonardo is an international development PFM advisor having extensive experience of working with SIDS. He is a director of PFMConnect.