African anti-corruption agencies’ digital platform usage

Posted by David Fellows and John Leonardo [1]

The release of TI’s 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) on 28 January 2021 has focused attention in many countries on current corruption levels. In a recent blog we outlined the possible role social media platforms offer for promoting online public engagement in the war against corruption. We also noted that in Africa there are strong positive correlations between social media user numbers and perceived corruption levels. In this blog we review African anti-corruption agencies (ACAs) digital platform, including social networking sites, usage. Additional regional analyses will be prepared over the next six months.

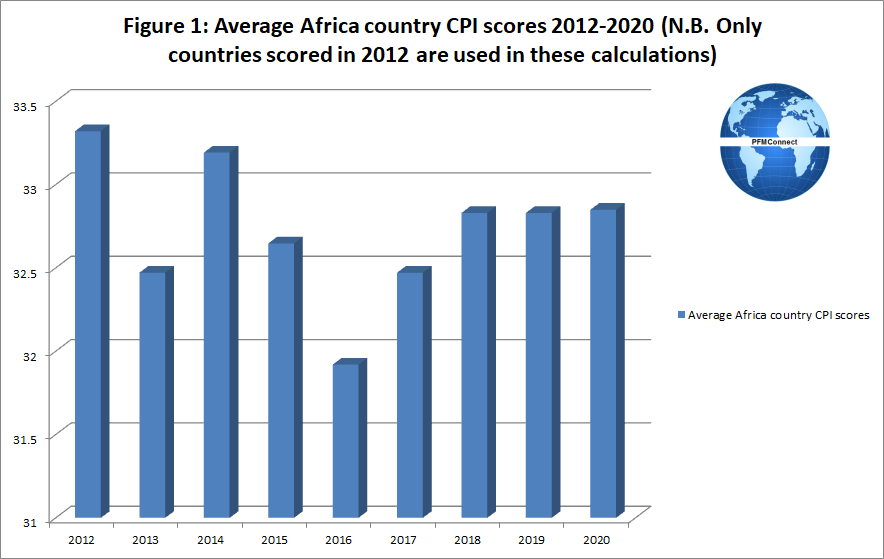

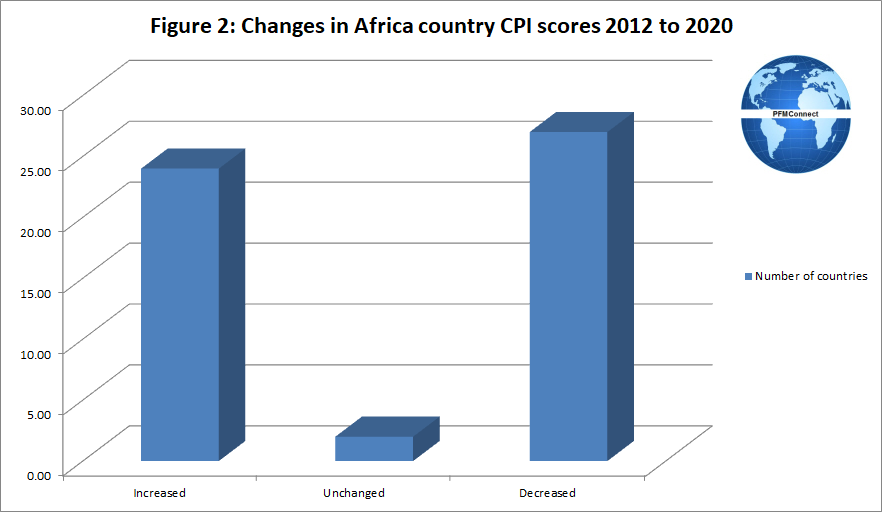

The 2020 CPI outcomes from an African perspective are disappointing as demonstrated by the trends revealed in Figures 1 and 2.

Websites and the social networking sites, Facebook and Twitter, are the digital platforms most frequently employed by African ACAs. Updates on ACA activities, developments affecting ACA operations and formal reports are featured on ACA digital platforms.

The United Nations Convention Against Corruption includes provisions relating to financial management and public reporting (Articles 9 and 10 – see Appendix). The extent of ACA compliance with these provisions has also been examined in this blog.

1. African ACAs digital platform usage

1.1 Website usage

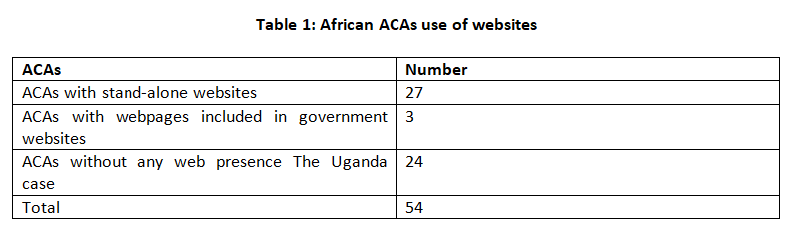

Details of the use of websites by African ACAs as at mid-January 2021 are presented in Table 1.

NB. Nigeria has two recognised ACAs with websites; Uganda has two recognised ACAs but only one has a website with the other using only social media sites. One Nigerian ACA with a website and the Ugandan ACA which only has social media sites are not included in Table 1 or Table 2 below.

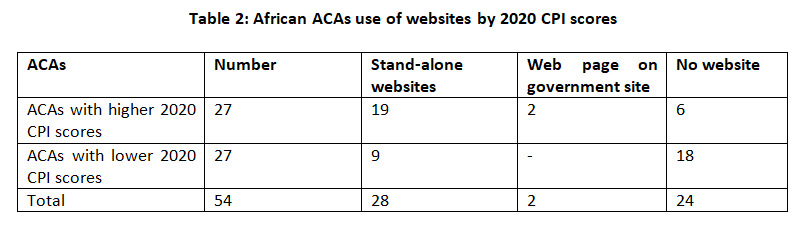

Details of the use of websites by African ACAs in countries with relatively higher and lower 2020 CPI scores are presented in Table 2.

Data was available for both 2020 CPI scores and 2020 UN E-government scores in 42 countries. There is a strong positive correlation between country 2020 CPI scores and 2020 UN E-government scores for the 23 countries where ACAs have websites (for which data is available); a strong negative correlation was found for the 19 countries without ACA websites.

1.2 Website visit activity

Actual visit numbers to ACA websites in the 2020 December quarter were annualised to provide annual visit estimates which were in turn divided by country internet user numbers to provide an indication of ACA website penetration levels.

The average derived ACA website penetration level for all ACAs was very low at 0.37%. The only favourable scores were recorded by Mauritius (5.9%) and Madagascar (1.9%).

1.3 Social media activity

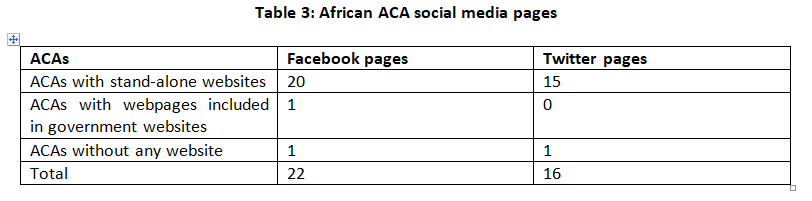

Social media follower information was analysed for ACAs with Facebook and Twitter pages using data available in mid-January 2021. Details of current Africa ACA social media pages are presented in Table 3. NB The Facebook and Twitter pages of the two Nigerian and Ugandan ACAs are included in the data presented in Tables 3, 4 and 5.

1.3.1 Facebook activity

Less than one half of the ACAs have Facebook pages.

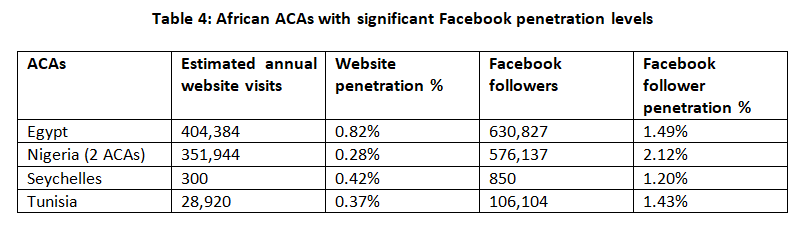

While the average Facebook penetration level for ACAs on a country basis (country ACA Facebook followers divided by total country Facebook subscribers) for the 20 countries was relatively modest at 1.06%, there were some notable exceptions.

Four of the six countries showing penetration levels in excess of the Facebook country ACA average of 1.06% also had follower numbers greater than estimated annual visits to their websites; details are presented in Table 4.

1.3.2 Twitter activity

The number of ACAs with Twitter pages is modest.

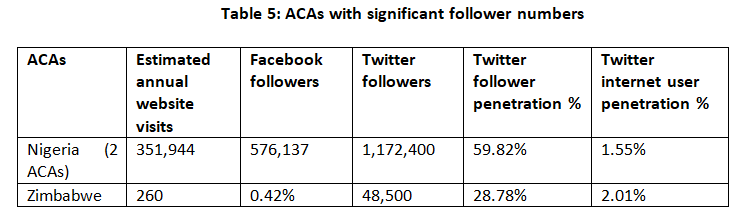

The average Twitter penetration level for ACAs on a country basis (country ACA Twitter followers divided by total country Twitter subscribers) for the 14 countries was, however, very high at 23.73%. Twitter country ACA penetration levels exceeded Twitter internet user penetration levels in six countries (Kenya, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Uganda and Zimbabwe).

Two of the countries recording above average country ACA Twitter penetration levels also had Twitter follower numbers that exceeded estimated annual visits to their websites; details are provided in Table 5.

While the majority of visits to the Nigeria and Zimbabwe ACA websites were made by local residents, the local resident proportion of Twitter followers for these ACAs is not known but it is assumed to be significant.

2. Reporting activity

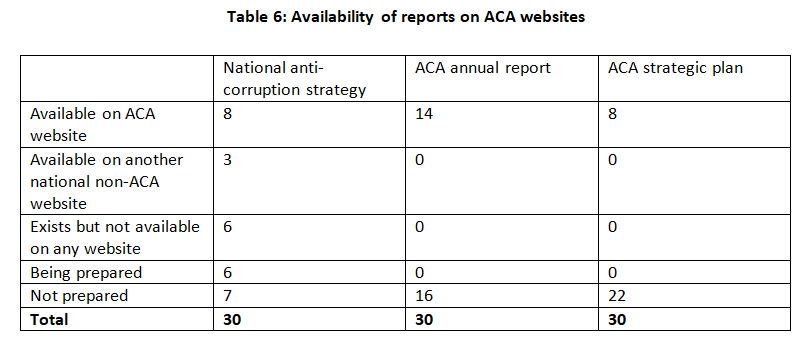

The availability of the following categories of key reports on ACA websites or on web pages of national government websites was examined:

- National Anti-Corruption Strategies

- ACA strategic plans

- ACA annual reports

Details of the availability of the above reports on ACA websites are presented in Table 6.

N.B. One Nigerian ACA with a website and the Ugandan ACA which only has social media sites are not included in Table 6.

Coverage of ACA digital platform activity in the above-mentioned reports, particularly those relating to social media, was also examined.

2.1 Publication of national anti-corruption strategies

Less than one-third of African ACAs with websites have published their respective national anti-corruption strategy on their website.

While the role of the media in national anti-corruption strategies is addressed in the eleven national anti-corruption strategies reviewed when preparing this blog, references to the role of social media are limited. Egypt’s National Anti-Corruption Strategy (2019-2024), Namibia’s National Anti-Corruption Strategy and Action Plan (2016-2019) and Sierra Leone’s National Anti-Corruption Strategy (2019-2023) make mention of social media activity,

The Namibia and Sierra Leone strategies outlined particular roles for social media activities.

Morocco’s ACA published a study in 2019 that assisted its preparation of a supporting communication strategy for its National Anti-Corruption Strategy (2015-2025). This study listed social media as one of the key success factors; viz. “The body must open up on social media and have “an online platform or space”, which it must maintain and control in order to get closer to its target segments and to be responsive”.

2.2 Publication of ACA annual reports

Only 14 of the 30 African ACAs identified in Table 6 have recently published their annual reports (or de facto annual reports) on their websites. Specific reference to the use of social media was made in 8 ACA annual reports.

The Ghana ACA noted in its 2018 annual report the use of social media by the Ghana chapter of Transparency International. The Kenya ACA provided statistics about website hits and social media followers in its 2018 annual report. In its 2017 annual report the Mauritius ACA gave a detailed discussion about its social media activity including its approach for using Facebook.

The executive summary for the Morocco ACA’s 2019 annual report noted that the ACA had to address its social media strategy in the course of developing its overall communication strategy.

Brief references to the use of social media were made in the Namibia (2019), Rwanda (2019), Sierra Leone (2019) and South Africa (2020) ACA annual reports.

2.3 Publication of ACA strategic plans

The modest number of ACA strategic plans that have been prepared recently is very surprising.

Five of the ACA strategic plans include specific references to the use of social media (Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, Sierra Leone and Togo).

Kenya, Malawi and Rwanda ACAs set out specific strategies and performance indicators for social media in their strategic plans. The Sierra Leone ACA set out specific strategies and progress markers while the Togo ACA set out details of the proposed launch of its website.

2.4 Overview of ACA online reporting activity

Assuming it is appropriate for all ACAs (including both Nigerian and Ugandan ACAs) to publish country anti-corruption strategies and their annual reports and strategic plans on their websites, the number of these documents that may be potentially published stands at 96 documents. Only 30 documents were published on ACA websites. This outcome falls short of the standards envisaged in the United Nations Convention against Corruption.

3. Social media performance and document publication correlations

ACA Facebook and Twitter subscriber penetration levels are weakly related to the number of ACA National Anti-Corruption Strategy, strategic plan and annual report publications placed on ACA websites.

While ACAs with relatively high Facebook and Twitter subscriber penetration levels have not generally been relatively energetic publishers of the above-mentioned reports, their social media posting activity has been sufficiently active to attract significant numbers of followers; this is most evident in the case of Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, Uganda and Zimbabwe.

ACA Facebook and Twitter subscriber penetration levels have, with a few exceptions, often substantially exceeded ACA website penetration levels.

4. Conclusion

The survey demonstrates a very limited level of publication on ACA websites of ACA reports in the three key categories identified in section 2.

It could add credibility to ACA professionalism and integrity to publish these reports even if some of the more sensitive detail concerning methodology and programming was omitted.

While ACA websites offer potential public engagement opportunities, social media activity has the potential for even higher engagement levels. It should be borne in mind that social media use in Africa, while a relatively recent phenomenon, is rapidly becoming extremely popular. The analysis demonstrates that while overall ACA use of social media is relatively limited, some ACAs have made considerable progress, particularly with the use of Twitter.

Those ACAs with websites but who currently do not have Facebook or Twitter pages should certainly consider these social networking sites as a means to gaining public confidence in anti-corruption activities and their cooperation in combatting anti-corruption investigations.

Appendix: United Nations Convention Against Corruption

Financial management and public reporting provisions

Article 9

Public procurement and management of public finances

2. Each State Party shall, in accordance with the fundamental principles of its legal system, take appropriate measures to promote transparency and accountability in the management of public finances. Such measures shall encompass, inter alia:

(a) Procedures for the adoption of the national budget;

(b) Timely reporting on revenue and expenditure;

(c) A system of accounting and auditing standards and related oversight;

(d) Effective and efficient systems of risk management and internal control; and

(e) Where appropriate, corrective action in the case of failure to comply with the requirements established in this paragraph.

Article 10

Public reporting

Taking into account the need to combat corruption, each State Party shall, in accordance with the fundamental principles of its domestic law, take such measures as may be necessary to enhance transparency in its public administration, including with regard to its organization, functioning and decision-making processes, where appropriate. Such measures may include, inter alia:

(a) Adopting procedures or regulations allowing members of the general public to obtain, where appropriate, information on the organization, functioning and decision-making processes of its public administration and, with due regard for the protection of privacy and personal data, on decisions and legal acts that concern members of the public;

(b) Simplifying administrative procedures, where appropriate, in order to facilitate public access to the competent decision-making authorities; and

(c) Publishing information, which may include periodic reports on the risks of corruption in its public administration.

[1] David Fellows is an international development PFM advisor who previously worked extensively in UK local government finance and in the Cabinet Office. He was a leader for the introduction of digital communication in UK public service delivery. John Leonardo is a PFM expert with extensive worldwide experience. They are both directors of PFMConnect, a consultancy providing online support in the fields of public finance and digital communication.