Corruption in the Caribbean (a US perspective)

Introduction

The United States State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices (“country reports”) strive to provide a factual and objective record on the status of human rights worldwide. The 2021 country reports were published on 12 April 2022.

Section 4 of the country reports provides an assessment of Corruption and Lack of Transparency in Government which addresses the extent to which a country’s law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials and the level of implementation of these laws.

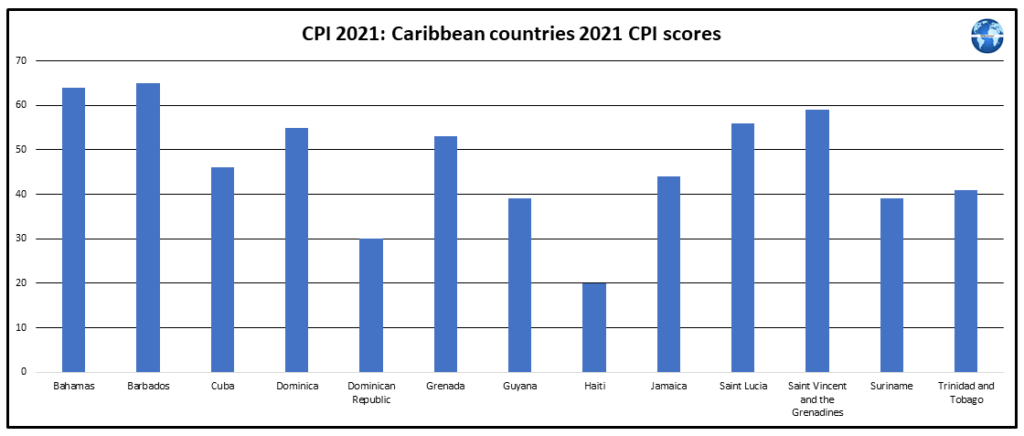

While 2021 scores for Caribbean countries published by Transparency International in their 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) report reveal material variations in anti-corruption performance, all Caribbean countries generally have criminal penalties for corruption by officials. The level of implementation of these laws, however, varies considerably. Inconsistent or ineffective implementation of penalties for corruption was reported in seven countries. Further discussion on corruption trends in Caribbean countries is provided here.

Details of the overview comments for Caribbean countries in the 2021 country reports are provided below.

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but full implementation of the law was hindered during the pandemic. Media reported several allegations of corruption against officials during the year. Media and private citizens reported government corruption was widespread and endorsed at the highest levels of government.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, and the government generally implemented the law effectively. There was limited enforcement of conflicts of interest related to government contracts. There were reports of government corruption during the year where officials sometimes engaged in cronyism and accepted small-scale “bribes of convenience” with impunity.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, and the government generally implemented the law effectively. In October the government passed the Prevention of Corruption Act, which provides for the prevention, investigation, and prosecution of acts of corruption, and applies to persons in both the public and private sectors. There were no reports of government corruption during the year.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively, and officials often engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption; however, the government did not implement the law effectively. There were numerous reports of government corruption, supported by a poorly regulated and opaque banking sector. The government was highly sensitive to corruption allegations and often conducted anticorruption crackdowns.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government implemented the law inconsistently. According to civil society representatives and members of the political opposition, officials sometimes engaged in corrupt practices.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, and in a change from previous years noted by independent observers, the government generally implemented the law effectively. The attorney general investigated allegedly corrupt officials.

NGO representatives said the greatest hindrance to effective investigations was traditionally a lack of political will to prosecute individuals accused of corruption, particularly well connected individuals or high-level politicians. Under President Abinader, however, the attorney general pursued a number of cases against public officials, including high-level politicians and their families, mostly from the previous administration but also including members of the current administration. Nonetheless, government corruption remained a serious problem.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, and the government generally implemented the law effectively. There were isolated allegations by the political opposition and some members of media regarding government corruption during the year, but none proved credible.”

“The law provides for criminal penalties for corruption by officials, and the government generally implemented the law effectively. There were isolated reports of government corruption during the year, and administration officials investigated these reports. There remained a widespread public perception of corruption involving officials at all levels and all branches of government, including the police and judiciary.”

“The law criminalizes a wide variety of acts of corruption by officials, including illicit enrichment, bribery, embezzlement, illegal procurement, insider trading, influence peddling, and nepotism. There were numerous reports of government corruption, and a perception of impunity for abusers. The judicial branch investigated several cases of corruption during the year, but there were no prosecutions. The constitution mandates the Senate (vice the judicial system) prosecute high-level officials and members of parliament accused of corruption, but the body had never done so. The government’s previous anticorruption strategy expired in 2019, and as of October there was no formal anticorruption strategy.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government generally did not implement the law effectively. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year, and corruption was a significant problem of public concern. Media and civil society organizations criticized the government for being slow and at times reluctant to prosecute corruption cases.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, and the government generally implemented the law effectively. Media and private citizens reported government corruption was occasionally a problem.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, and the government generally implemented these laws, but not always effectively. There were isolated reports of government corruption during the year.”

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not always implement the law effectively.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, and the government implemented the law effectively at times. The 2017 Anti-Corruption Law, which was unanimously approved by the National Assembly, had not been implemented as of October, but authorities stated they were able to prosecute cases of corruption based on existing law.

Corruption cases reported to the Attorney General’s Office were investigated. There were numerous accusations from political opponents, civil society, and media that officials engaged in corrupt practices.”

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not enforce the law effectively, and officials sometimes engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. There were credible reports of police and government corruption during the year.”

Conclusion

The laws in Caribbean countries generally provide relatively robust criminal penalties for corruption by officials.

The above-mentioned country reports, however, reveal there are currently significant variations in Caribbean government efforts to implement legislation covering criminal penalties for corruption.