Author: David Fellows

Governance of public affairs is a complex topic. It includes the processes by which decisions are made, the means by which service performance is assessed, the standards of behaviour to which public servants are held, the transparency applied to public life and the extent to which ordinary citizens are engaged in policy-making. In this respect, developing countries provide a wealth of expertise and examples of outstanding practice, research projects, and reform programmes.

In this post I propose an approach to governance reform in developing countries that is owned and developed more extensively through multinational collaboration, and that uses digital media as a basis for that collaboration. This is not to suggest that development partners should be excluded from generating ideas or providing support but that developing countries should become more dominant orchestrators of their own development through more effective collaboration.

Working with an International Perspective

Each nation requires its own strategies and implementation plans for governance reform, reflecting its specific needs, capacities, cultures, geographies and priorities. Nevertheless, multinational collaboration can offer a valuable combination of experience, ideas and expertise from diverse perspectives. At the centre of such an approach would be those who are responsible for achieving administrative reform, both civil servants and politicians, and who are intimately familiar with the challenges of the operational situation.

Such an approach would require an open and honest sharing of key problems and possibilities, the reality of progress made and the means by which achievements are being realised. Research could be shared at an early stage, development programme progress could be followed as it is rolled out and promising initiatives could be emulated promptly. Practical solutions could be sought to common problems, including mutual dependences.

This shared approach could involve officials, academics, staff from development agencies and the private sector, journalists and other experts. Technology can facilitate virtual exchanges that would not otherwise be feasible due to time, cost, and travel restrictions. It could enable the engagement of those best placed to assist, rather than those who are most readily available. In short, digital technology is an excellent medium for bringing the most appropriate combination of people together in a low-cost, time-efficient manner.

There are very many collective organisations in most if not all regions of the world, including organisations with broad national representational remits, organisations consisting of specific types of institutions, and professional bodies. The purpose of this proposal is not to supplant these organisations, but to use them as a source of expertise, conduits for dissemination and platforms for discussion. Regional collaboration whether of formal groupings or ad hoc alliances can also provide a highly effective means by which these proposals can be approached in their entirety.

New Ways of Working using Digital Technology

There are four basic strands to my proposed approach: (i) collaborative development arrangements; (ii) expert advice and mentoring; (iii) professional training for public servants; and (iv) public transparency and engagement.

(i) Collaborative development. Central to this proposal is the notion of collaboration: sharing current practice; learning from research and reform programmes; and identifying more effective ways of working through collective consideration. Relevant subject matter could include: public procurement; budgeting and performance management; auditing and risk management; broad-based annual reporting; the appointment of public officials; the conduct of elections; declarations for public office; small business development; cross border trading; taxation policy and the administration of justice. Broader themes are also relevant, such as strategic planning; combatting corruption and equality of opportunity.

A key aspect of the collaborative approach is to engage a broad range of relevant people to contribute their ideas, experiences and judgements. The emphasis should be on how national priorities might be identified, reform programmes constructed, and viability tested. Their objective would be the creation of reasonably effective solutions that are affordable, feasible and sustainable.

The use of digital technology would allow flexible connectivity between people and ready access to information resources. Databases capturing a wide variety of policies, plans, reviews, process descriptions and standards would need to be constructed and made available for interrogation. Updatable schedules of financial and performance data would be required together with platforms to facilitate multiple authoring of documents. Working group meetings could be conducted over video conferencing systems offering document display and a record of proceedings.

(ii) Expert advice and mentoring. Beyond large group collaborations, the proposal also offers the opportunity for knowledge and experiences to be shared on a more personal basis. The key technological contributions here would be email, chat rooms and video conferencing with some use of databases as discussed under (i) above.

(iii) Professional training for public servants. Professional training is an essential aspect of public service development. However, traditional training methods can be highly expensive when physical attendance is required and can make significant demands on the student’s time away from the office.

‘Open university’ approaches to further education have been in operation for decades in many countries and new technology has given them a boost [1]. There is no reason why the model cannot be extended to suit the particular professional development needs of public servants from developing countries.

Digital technology can enhance the learning experience with video packages, interactive learning modules, online assessments, conventional study material, chat rooms and email exchanges together with video conferencing for tutorial sessions. Existing study programmes (e.g., World Bank courses) could be incorporated. Academics from major institutions around the world, experts from development agencies and specialists from international centres of excellence could be approached to lend support, providing a rich learning experience. It is possible that some existing public service training institutions could provide the basis for this type of provision.

Financial support for traditional training facilities has tended to fall out of favour with development partners. Perhaps this should be reconsidered using an evidenced-based approach to the value derived. A recent study [2] undertaken by PFMConnect provides substantial support for the feasibility of such an approach.

(iv) Public transparency and engagement. This can equip citizens to contribute ideas for the development of public service and hold officials to account for their judgement, integrity and effectiveness. Going further, it can also help to reduce costs and improve service benefits, root out corruption, and create confidence in public institutions.

This process of accountability and engagement can be effectively achieved through official websites, chat rooms, email and social media. There is considerable scope for all governments to improve two-way communication with their citizens. A professional training institution as discussed above should seek to play a leading role in advancing key developments in administrative reform, including public transparency.

Key Technical Considerations

This proposal mainly concerns the infrastructure available to central government services in capital cities, as central government offices are the principal subject of these proposals. In this respect there is already a fairly high standard of general internet connectivity and the capacity to implement facilities of the kind required. The public engagement aspects must, however, rely on whatever public networks are available in a particular locality and these can be expected to improve over time.

In terms of government offices, there appear to be three principal technological issues. Firstly, individual offices need to have appropriate internal facilities. Secondly, there will need to be agreement to a range of key considerations concerning the digital architecture, service providers and core software products. Some issues must be decided internationally and some can be left to local discretion. For example, video conferencing requires basic software decisions to be made on behalf of all users with operating systems and browsers having the capacity to support the chosen software but beyond this there can be considerable desktop flexibility. Thirdly, it may be useful to establish document standards for certain purposes [3].

A balance would need to be struck between the sharing of information across a broad network of participants and the need for confidentiality and security over some material. Clearly such a proposal will not take root if it is based on stipulations that are highly complex and expensive. An evolutionary approach is clearly required.

Conclusion

In a previous blog covered by the World Policy Journal the author and colleague John Leonardo set out the case for governance reform in developing countries in order to reduce corruption and thereby improve economic performance and public service delivery.

Shifting the balance of responsibility and organising power for governance reform towards developing nations could give this agenda new impetus. An imaginative use of digital technology could enrich the inclusivity and practicality of such an approach.

This is a very tentative proposal. I have not started to discuss whether it would constitute a unified system or a series of ad hoc arrangements; how such a proposal would gain traction; and how the system would be financed. Observations and reactions would be welcome.

David Fellows is Co-principal of PFMConnect.

Thanks are extended to Chris Fellows of ITI Europe for his views on the application of digital technology.

[1] See this example from a British university: http://www.wbs.ac.uk/courses/mba/distance-learning/teaching/

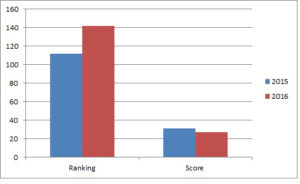

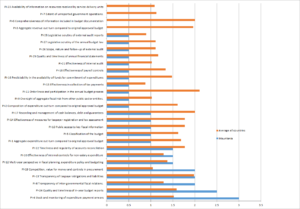

[2] Commonwealth Africa Anti-Corruption Programme Evaluation – see http://blog-pfmconnect.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Anti-Corruption-Africa-Programme-Evaluation-Feb-2017.pdf

[3] For instance: Horizon 2020 EU programs must include a deliverable called “data management plan” that, in part, describes the kinds of formats that will be adopted within the consortium. See http://www.sussex.ac.uk/library/researchdatamanagement/create/biddingforfunding/horizon2020dataplan and http://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/data/ref/h2020/grants_manual/hi/oa_pilot/h2020-hi-oa-data-mgt_en.pdf)

Background

Background