Corruption in Eastern Europe (a US perspective)

Introduction

The United States State Department’s Country Reports on Human Rights Practices (“country reports”) strive to provide a factual and objective record on the status of human rights worldwide. The 2021 country reports were published on 12 April 2022. Section 4 of the country reports provides an assessment of Corruption and Lack of Transparency in Government which addresses the extent to which a country’s law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials and the level of implementation of these laws. This blog examines current enforcement action to address corruption in Eastern Europe by officials.

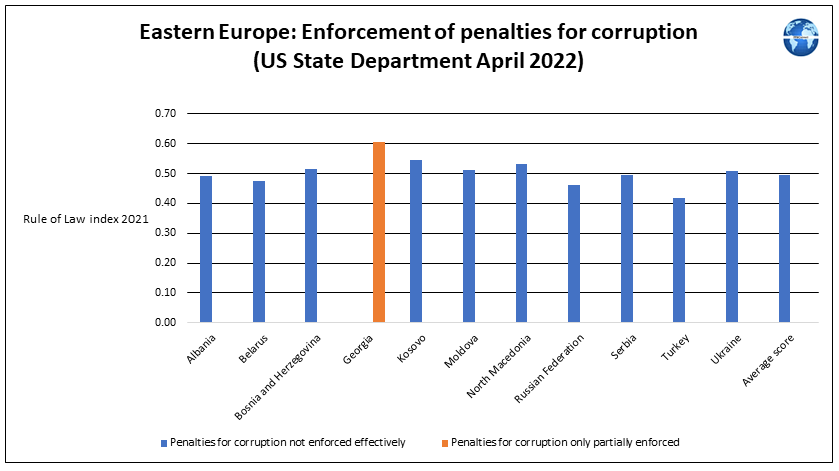

Scores for Eastern European countries published by Transparency International in their 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) report demonstrate that Eastern Europe was ranked second out of global regions in terms of improvements in CPI scores during 2012-2021. Improvements in CPI scores in excess of the global average were recorded by the majority of Eastern European countries during the 2012-2021 period. The country reports for Eastern European countries reveal that only one Eastern European country was making progress in effectively implementing current criminal penalties for corruption by officials (and only on a partial basis). Further discussion on corruption trends in Eastern European countries is provided here.

Details of the overview comments for Eastern European countries in the 2021 country reports are provided below.

Albania

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by public officials and prohibits individuals with criminal convictions from serving as mayors, parliamentarians, or in government or state positions, but the government did not implement the law effectively. Corruption was pervasive in all branches of government, and officials frequently engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. Through September, the Special Prosecution Office against Corruption and Organized Crime (SPAK) announced that it had opened investigations and brought charges against several public officials, including former ministers, mayors, sitting judges and prosecutors, former and sitting judges of the Constitutional Court’s Vetting Appeal’s Chamber, former judges of the Supreme Court, and officials in the executive branch. As of September, one judge, two prosecutors, one mayor, and the former procurement director at the Ministry of Interior were indicted on abuse of office or corruption charges.

The constitution requires judges and prosecutors to undergo vetting for unexplained wealth, ties to organized crime, and professional competence. The Independent Qualification Commission conducted vetting, and the Appeals Chamber reviewed contested decisions. The International Monitoring Operation, composed of international judicial experts, oversaw the process. As of November, 125 judges and prosecutors were dismissed, 103 confirmed, while 48 others had resigned rather than undergo vetting. As of July, 173 judges and prosecutors were dismissed, 148 confirmed, while 89 others had resigned or retired.

Several government agencies investigated corruption cases, but limited resources, investigative leaks, real and perceived political pressure, and a haphazard reassignment system hampered investigations.”

Armenia

“The law provides criminal penalties for official corruption. Following the 2018 “Velvet Revolution,” the government opened investigations that revealed systemic corruption encompassing most areas of public and private life. The government launched numerous criminal cases against alleged corruption by former high-ranking government officials and their relatives, parliamentarians, the former presidents, and in a few instances, members of the judiciary and their relatives, with cases ranging from a few thousand to millions of dollars. Many of the cases continued, and additional cases were reported regularly. The government also initiated corruption-related cases against several current government officials and members of the judiciary.

In addition to integrity checks of nominees, the Corruption Prevention Commission exercised its powers to review sitting judges’ asset declarations and to communicate to law enforcement information that may indicate a crime. As a result, three disciplinary, three administrative, and one criminal case had been initiated.

Authorities took measures to strengthen the institutional framework to fight corruption, including establishing the Anticorruption Committee, which served as the primary law enforcement body dealing with corruption. The committee began operations in October and initiated several cases, such as charging former chief of police Vladimir Gasparyan with legalizing criminally obtained property worth more than two billion drams ($4.1 million) and other criminal acts.”

Azerbaijan

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively and officials often engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. While the government made some progress in combating low-level corruption in the provision of government services, there were continued reports of corruption by government officials, including those at the highest levels.

Transparency International and other observers described corruption as widespread. There were reports of corruption in the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. For example, in six reports on visits made to the country between 2004 and 2017, the CPT noted that corruption in the country’s entire law enforcement system remained “systemic and endemic.” In a report on its most recent visit to the country in 2017, for example, the CPT cited the practice of law enforcement officials demanding payments in exchange for dropping or reducing charges or for releasing individuals from unrecorded custody. These problems persisted throughout the year. Media reported that on April 26, the head of the Shamkir Executive Committee Alimpasha Mammadov was detained on corruption-related charges.

Similar to previous years, authorities continued to punish individuals for exposing government corruption. For example, during the year police detained two civil society activists who were then turned over to the Main Department to Combat Organized Crime of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. The two activists were preparing a media story about government corruption. Main Department to Combat Organized Crime officials reportedly tortured one of these individuals.”

Belarus

“The law provides criminal penalties for official corruption, and the government appeared to prosecute regularly officials alleged to be corrupt. The World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators reflected that corruption was a serious problem in the country. In 2019 the Council of Europe’s Group of States against Corruption (GRECO) declared the country noncompliant with its anticorruption standards. The government did not publish evaluation or compliance reports, which according to GRECO’s executive secretary, “casted a dark shadow over the country’s commitment to preventing and combating corruption and to overall cooperation with GRECO.” In 2019 GRECO’s executive secretary repeated its concerns regarding the country’s “continuous noncompliance.””

Bosnia and Herzegovina

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively nor prioritize public corruption as a serious problem. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year. Courts have not processed high-level corruption cases, and in most of the finalized cases, suspended sentences were pronounced. Officials frequently engaged in corrupt practices with impunity, and corruption remained prevalent in many political and economic institutions. Corruption was especially prevalent in the health and education sectors, public procurement processes, local governance, and public administration employment procedures.

The government has mechanisms to investigate and punish abuse and corruption, but political pressure often prevented the application of these mechanisms. Observers considered police impunity widespread, and there were continued reports of corruption within the state and entity security services. There are internal affairs investigative units within all police agencies. Throughout the year, mostly with assistance from the international community, the government provided training to police and security forces designed to combat abuse and corruption and promote respect for human rights. The field training manuals for police officers also include ethics and anticorruption training components.”

Georgia

“The law provides criminal penalties for officials convicted of corruption. While the government implemented the law effectively against low-level corruption, NGOs continued to cite weak checks and balances and a lack of independence of law enforcement agencies among the factors contributing to allegations of high-level corruption. NGOs assessed there were no effective mechanisms for preventing corruption in state-owned enterprises and independent regulatory bodies. NGOs continued to call for an independent anticorruption agency outside the authority of the State Security Service, alleging its officials were abusing its functions.

On September 8, Transparency International/Georgia stated the country had “impressively low levels of petty corruption combined with near total impunity for high-level corruption.” The country also lacked an independent anticorruption agency to combat high-level corruption.

Several months after resigning, in a May 31 interview former prime minister Giorgi Gakharia noted that the country’s “biggest challenge is weak institutions. When institutions are weak, corruption and nepotism represent a problem.”

The Anticorruption Coordination Council included government officials, legal professionals, business representatives, civil society, and international organizations. In March amendments to the Law on Conflict of Interest in Public Service moved responsibility for assisting the work of the Anticorruption Council from the Justice Ministry to the Administration of the Government, headed by the prime minister but separate from the Prime Minister’s Office. Formation of the relevant secretariat was underway at year’s end. The last Anti-Corruption Strategy and Action Plan was developed by the council in 2019. The council has not met since it was moved under the government’s administration.

Transparency International/Georgia, in its October 2020 report Corruption and Anti-Corruption Policy in Georgia: 2016-2020, noted the government annually approves national action plans to combat corruption. It reported some shortcomings, however, including ineffective investigations of cases of alleged high-level corruption. Although the law restricts gifts to public officials to a maximum of 5 percent of their annual salary, a loophole allowing unlimited gifts to public officials from their family members continued to be a source of concern for anticorruption watchdogs. In January, Transparency International/Georgia noted that the country’s anticorruption reforms did not progress.

As of March, Transparency International/Georgia listed 50 uninvestigated high-profile cases of corruption involving high-ranking public officials or persons associated with the ruling party.”

Kosovo

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively. There were reports of government corruption. Officials sometimes engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. A lack of effective judicial oversight and general weakness in the rule of law contributed to the problem. Corruption cases were routinely subject to repeated appeal, and the judicial system often allowed statutes of limitation to expire without trying cases.”

Moldova

“While the law provides criminal penalties for official corruption, the government failed to implement the law effectively, and officials frequently engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. Despite some improvement, corruption remained a serious problem. Corruption in the judiciary and other state structures was widespread. Addressing corruption was one of the main promises of the new government formed after the July 11 snap parliamentary elections. One of the new government’s first steps was to amend the Law on the Prosecutor’s Office to allow the dismissal of the prosecutor general for “unsatisfactory performance” or his suspension in the event of a criminal case against him. Opposition parties contested the law, which was upheld by the Constitutional Court on September 30.

The law authorizes the National Anticorruption Center to verify wealth and address “political integrity, public integrity, institutional integrity, and favoritism.” The National Integrity Authority (NIA), which was formed to check assets, personal interests, and conflicts of interest of officials, was not fully operational due to prolonged delays in selecting integrity inspectors, as required by law. The PAS harshly criticized both the National Anticorruption Center (NAC) and the NIA for lack of action in investigating corrupt officials. Civil society organizations maintained that the NIA and NAC were still ineffective in fighting corruption. In November PAS members of parliament passed a bill that allows parliament to directly appoint or fire the director of the NAC. On November 19, parliament heard the legal committee’s report regarding NAC activity and fired the center’s director. Another bill voted by PAS on October 7 more clearly defines the role of NIA and enhances its operational capacity. On September 21, the Constitutional Court struck down the December 2020 law that limited NIA powers.”

Montenegro

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government did not implement the law effectively, and corruption remained a problem. Corruption and low public trust in government institutions were major issues in the 2020 parliamentary elections. There were numerous media and NGO reports that the new government upheld old patterns and that the public viewed corruption in hiring practices based on personal relationships or political affiliation as endemic in the government and elsewhere in the public sector at both local and national levels, particularly in the areas of health care, higher education, the judiciary, customs, political parties, police, the armed forces, urban planning, the construction industry, and employment.

The Agency for the Prevention of Corruption (APC) was strengthened through continued capacity-building activities and technical assistance during the year, but domestic NGOs were critical of the agency’s lack of transparency and described periodic working group meetings with it as cosmetic and superficial. The European Commission noted that problems related to APC’s independence, priorities, selective approach, and decision quality continued.

Agencies tasked with fighting corruption acknowledged that cooperation and information sharing among them was inadequate; their capacity improved but remained limited. Politicization, poor salaries, and lack of motivation and training of public servants provided fertile ground for corruption.”

North Macedonia

“The law provides criminal penalties for conviction of corruption by officials. The government generally implemented the law, but there were reports officials engaged in corruption. NGOs stated the government’s dominant role in the economy created opportunities for corruption. The government was the country’s largest employer. According to the Minister of Information, Society, and Administration, as of the end of December 2020, there were 131,183 persons employed in the public sector. Previously, some individuals on the government’s payroll did not fill real positions in the bureaucracy. On January 19, the government adopted a plan for assigning 1,349 civil servants paid by the Ministry of Political Systems and Community Relations – who at that time did not encumber a real position – to specific jobs across 237 government institutions. On April 27, the government dismissed the State Market Inspectorate director, Stojko Paunovski, for refusing to enforce the government decision assigning 35 civil servants to his institution.

On April 18, parliament adopted the 2021-2025 National Strategy for Countering Corruption and Conflict of Interest, along with the implementing action plan. On July 14, the government adopted a 2021-2023 National Strategy for Strengthening Capacities for Financial Investigations and Confiscation of Property as part of its plan for fighting corruption and provided for a commission to monitor the strategy’s implementation.”

Russia

“The law provides criminal penalties for official corruption, but the government acknowledged difficulty in enforcing the law effectively, and officials often engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year.”

Serbia

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption by officials, but the government generally did not implement the law effectively, and convictions for high-level official corruption were rare. According to an April public opinion survey by the CRTA, 65 percent of citizens believed there was significant corruption in the country, the majority believed the state was ineffective in fighting corruption, and 62 percent believed the government put pressure on individuals, media, or organizations that identified cases of corruption in which members of the government were reportedly involved. There was a widespread public perception that the law was not being implemented consistently and systematically and that some high-level officials engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. There were numerous reports of government corruption during the year. The government reported an increase in prosecution of low- to mid-level corruption cases, money laundering, and economic crimes cases. High-profile convictions of senior government figures for corruption, however, were rare, and corruption was prevalent in many areas and remained a problem of concern.

The Freedom House Nations in Transit 2021 report described the country as a “hybrid regime” rather than a democracy due to reported corruption among senior officials that had gone unaddressed in recent years. While the legal framework for fighting corruption was broadly in place, anticorruption entities typically lacked adequate personnel and authority and were not integrated with other judicial, legal, or other entities, which inhibited information and evidence sharing with the prosecution service. Freedom House’s 2020 report on the country noted the work of the Anticorruption Agency (ACA) was undermined in part by the ambiguous division of responsibilities among other entities tasked with combating corruption. Freedom House downgraded the country’s political pluralism and participation score in part based on the credible reports that the ACA did not thoroughly investigate dubious political campaign contributions, including the use of thousands of proxy donors to bypass legal limits on individual campaign donations and disguise the true source of funding. The GRECO 2020 Annual Report found that the country had not fully implemented anticorruption measures related to the recruitment and rules of conduct governing members of parliament, judges, and prosecutors.

EU experts noted continuing problems with the overuse of the vague “abuse of office” charge for alleged private-sector corruption cases. Despite the government’s publicly stated commitment to fight corruption, both the country’s Anticorruption Council and the NGO Transparency Serbia continued to point to a lack of governmental transparency.”

Turkey

“While the law provides criminal penalties for conviction of official corruption, the government did not implement the law effectively, and some officials engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. Parliament entrusts the Court of Accounts, the country’s supreme audit institution, with accountability related to revenues and expenditures of government departments. Outside this audit system, there was no dedicated regulator with the exclusive responsibility for investigating and prosecuting corruption cases and there were concerns regarding the impartiality of the judiciary in the handling of corruption cases. According to Transparency International, the public procurement system has consistently declined in transparency and competitiveness, with exceptions to the Public Procurement Law widely applied.

While opposition politicians frequently accused the ruling party of corruption, there were only isolated journalistic or official investigations of government corruption during the year. Journalists and civil society organizations reported fearing retribution for reporting on corruption issues. Authorities continued to pursue criminal and civil charges against journalists reporting on corruption allegations. Courts and RTUK regularly blocked access to press reports regarding corruption.

In May the state-run Anadolu Agency fired reporter Musab Turan after he asked government officials about corruption allegations against Minister of Interior Suleyman Soylu during a press conference. Anadolu Agency issued a statement that Turn was fired for lacking “journalistic principles” and propagating “political propaganda.” The statement also said that Anadolu requested that prosecutors open a terrorism investigation into Turan. Fahrettin Altun, the presidency’s communications director, wrote on Twitter, “Those who seek to harm the respectability of our state will pay the price.””

Ukraine

“The law provides criminal penalties for corruption. Authorities did not effectively implement the law, and many officials engaged in corrupt practices with impunity. While the number of reports of government corruption was low, observers noted corruption remained pervasive at all levels in the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. From January 1 to June 30, the National Anticorruption Bureau of Ukraine launched 336 investigations that resulted in 25 indictments against 43 individuals. Accused individuals included public officials, heads of state-owned enterprises, one judge, and others.

On September 5, the High Anticorruption Court (HACC) announced that in the previous two years it had convicted 10 judges for a range of offenses, including soliciting bribes, lying in financial declarations, and abuse of office. The court sentenced the judges to between two and nine years in prison, deprived them of the right to hold office for a period of three years, and confiscated property. In 2020 and during the year, the HACC sentenced 36 officials to imprisonment on corruption-related charges. Anticorruption bodies continued to face pressure from antireform elites and oligarchs in the form of misinformation campaigns and political maneuvering that undermined public trust and threatened the viability of the institutions. Human rights groups called for increased transparency and discussion regarding proposed changes to these bodies, particularly respecting procedures for appointments to leadership positions. As of September 13, it was widely held that the selection process for the new head of the Special Anticorruption Prosecutor’s Office remained stalled due to political interference.

Human rights groups claimed another threat to the anticorruption infrastructure came from the Constitutional Court, where antireform interests exercised undue influence on judges. Parliament amended some provisions of anticorruption legislation that had been overturned by Constitutional Court decisions in 2020, and legislation to safeguard the independence of the National Anticorruption Bureau was adopted by parliament on October 19. Also pending was a review by the Constitutional Court on the constitutionality of the High Anticorruption Court law.

On July 13, parliament adopted legislation to relaunch the High Qualification Commission of Judges and High Council of Justice (HCJ), bodies that control the hiring of judges and judicial self-governance, respectively, and that judicial reform groups characterized as influenced by corrupt interests. Implementation of the law governing vetting of HCJ members, however, faltered within weeks of enactment, when the Council of Judges refused to nominate at least one candidate to serve on the HCJ Ethics Council, which is envisioned to comprise three legal experts nominated by international partners and three Ukrainian judges nominated by the Council of Judges. On October 23, the Council of Judges nominated four judge candidates, but legal experts noted the Supreme Court had referred the judicial reform law to the Constitutional Court to assess its constitutionality.”

Conclusion

The country reports for Eastern European countries demonstrate an unsatisfactory outcome with no countries in the region well placed to fight against corruption by officials.

Significant challenges in combatting corruption in Eastern Europe are likely to remain until there are material improvements in all countries in their ability to enforce criminal penalties for corruption.